I used to own a dictionary.

As a child I had a big green and white one, with colored pictures on

creamy white pages. It was the kind of

book that just felt good to flip through.

There was a huge purple speckled paged dictionary at my grandmother’s

house. We had pocket dictionaries and pre-smartphone, hand held techno-dictionaries.

In the library at my high school and in the public library too a dictionary

that would be too big to fit on a shelf, sat like an idol on a pedestal waiting

for the faithful.

Now I don’t think there is a dictionary in this house. Not a paper one. We do still have books. At every corner, spilling off every shelf,

nightstand, corner of flat space, but not a dictionary. We have Google instead, and Wikipedia, and

the red squiggle line in Word.

The dictionaries as symbols of languages in my life come

with contexts and histories that shape some of who I am. As much as any words themselves it’s the context

surrounding them that create meanings. In

my read of another chapter of Baker’s Sexed Texts this week she wrote about how

more contemporary researchers in gender and language studies have moved to see these social constructs of gender through,

especially the importance of context and ways that gender is taken on,

particularly through language.

In a chapter of her book, Feminist Practice &

Poststructuralist Theory, Chris Weedon, creates very particular constructions

of poststructuralist feminism and other feminisms (radical, Marxists, etc). She builds a history of understanding the way

women have been positioning through either negation, essentialized or fixed particularly

through the projects of rationalism and humanism. For Weedon poststructural lenses offer a more

complicated, multiplicitious, power conscious and context-based understanding of

gender. As I spent time yesterday in

Atkins Library interacting with three feminist dictionaries, I was thinking of

the work similar to reading Weedon that this genre study into feminist dictionaries does for me as a

student of feminism. As Weedon tours

feminisms and names the theories at work for constructing gender and difference,

the dictionaries, work as part of a metagenre, which shows the thinking behind

language in particular conversations. In looking at dictionaries of Maggio,

Kramarae and Treichler and Daly, I construct for myself understandings of how

language works for these three feminists, as representative of larger movements

in the field.

MJ Hardman writes about the material power of language in

her work with speakers of the Jaqi language.

She explores the ways the non-sexist language constructs the everyday

lives and power structures for and of women, and the contradictory structures

created when outside languages (of conquerors) moves into the context. She explores the particular contexts of

words, including the people and location and history surrounding the social

work they are associated with. In

looking next at selections from feminist dictionaries, I am wondering about the

ways context is constructed or hidden by dictionaries.

The Nonsexist Word Finder: A Dictionary of Gender-Free Usage

(Maggio, 1989)

Maggio’s describes her goal to change words that are no

longer useful, while for Maggio this may or may not change social issues, the

language itself can become more socially useful.

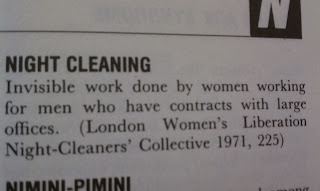

A Feminist Dictionary (Kramarae & Treichler, 1996)

The excerpts below exemplify the goals of Kramarae and

Treichler to counter traditional dictionaries by making visible women’s words,

critique of languages of privilege, make visible multiple ways of knowing, to

counter traditional processes of authorization and to inspire research and

further thinking.

Webster’s First new Intergalactic Wickedary of the English

Langauge (Daly, 1987)

Below are examples of Daly’s work in this dictionary to

connect words to women, through unbinding their definitions and disrupting the

contexts and histories attached to them, making them undone.

Commonly these dictionaries displace for the most part language from

everyday life, partly fixing it in the traditional format of dictionary. Each counters the dominant dictionary form,

though: Maggio by demanding word replacement and change. Kramarae and Treichler by exploding each “definition”

with multiple forms and authors. And

Daly by critiquing and revisioning dominant forms for new and subversive

purposes.

In a critique of Mary

Daly’s work by Jane Hedley notes the parallels and differences in theory and political

work between Daly and Andrienne Rich.

Hedley sees Daly’s binary-flipping work in revisioning language as

useful only to a point, while Rich’s revisioning of language use as connected

to everyday life as having more impact on the situations of women. I think Hedley’s critique works to some

extent for all three feminist dictionaries, possibly as they are contained by

the form of dictionary in itself, even as they undo the form. I wonder to what extend Elgin’s working of

theory through novel puts power back into the everyday experiences (even if

they are not completely common to my world everydays) of women. Does this drawing on the day to day do

similar political work to Adrienne Rich, or being fantastical are there still

limits? In some way the fantasy element

may do greater work than ethnography or dictionary building or research article,

since Elgin lays precise claim to the fact that her story, her theories the

lives of these women are completely fiction.

The rest, I think Weedon would say (and sometimes me), is fiction too-

it just pretends to be non.

No comments:

Post a Comment